Article originally featured in USA Today

As a professional caregiver, Bill Glover saw firsthand the impact of social isolation on his clients during the pandemic.

Many are elderly and live with some form of dementia, which includes a range of medical conditions caused by abnormal brain changes that can trigger memory loss, impair judgment and limit social skills.

Glover spends several hours a week assisting clients with basic tasks in their homes, such as exercise. He has worked as a caregiver for the last seven years with Home Instead, one of the largest in-home care providers in the country. The company offers home-based caregiving services for older adults who need personalized non-medical help and companionship to live safely in their homes.

Many older adults were already isolated. COVID restrictions made it worse.

Since the pandemic started more than 700,000 deaths have been reported. People ages 65 and older represent nearly 80% of all COVID-19 deaths as of Sept. 29, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. And while severe illness from coronavirus remains a critical concern for elderly patients, Glover said isolation led to a worrisome worsening of symptoms among clients living with memory loss and other forms of cognitive impairment.

“These people need to see somebody,” Glover said. “I saw so many people deteriorate as a result of that (isolation) because nobody anticipated; we didn't know what was coming.”

Even before the pandemic, older adults were already prone to isolation due to chronic illness, the loss of family and friends and living alone. Lockdowns and other restrictions aimed at reducing the spread of COVID-19 compounded the problem for seniors leading to a spike in symptoms such as stress, anxiety and depression in that age group, according to a study published in Nature in January.

Older adults with dementia living in long-term care were more likely to experience “additional distress,” greater agitation, boredom and loneliness due to the inability to receive regular visits from friends and family members, according to the study.

Social interaction 'very important' for patients with memory loss

That’s why social interaction from someone that is familiar with the patient is important, said Dr. Walter Royal, the director of the Neuroscience Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

“It’s pretty clear that interactions are very important for decreasing risk and severity of the delirium that occurs in a large percentage of patients. For someone with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, the isolation that can occur can lead to people feeling disconnected and developing worse mental status,” he said.

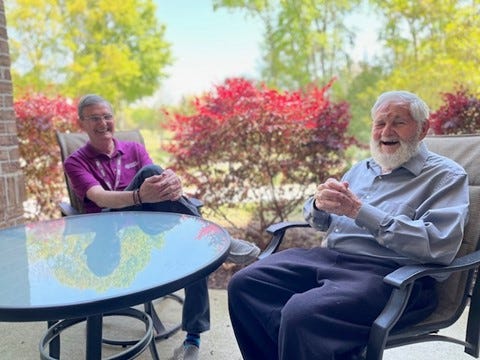

Bill Glover (left) a home caregiver with Home Instead visits Jean-Marc Bollag (right) at his home in Daniel Island, S.C. Glover spends several hours each week visiting clients, helping them with basic tasks around their homes.

Experts say safety measures during the pandemic have also created delays in the ability to diagnose different types of dementia in their early stages. Only one in three people with dementia and their caregivers had in-person access to a clinician throughout the pandemic, according to the 2021 World Alzheimer’s Report.

It’s estimated that about 6.2 million Americans are currently living with Alzheimer’s or some other form of dementia. Experts say that number will grow as the population of people older than 65 increases from 58 million in 2021 to 88 million in 2050, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

'A really devastating situation'

When visits to long-term care facilities were highly restricted, care providers were forced to get creative, said Beth Kallmyer, the vice-president for Care and Support at the Alzheimer’s Association. Family members were limited to phone or video chats with their loved ones. In-person visits when possible were usually held at a distance with family members visiting their loved ones standing outside the facility.

But for patients further along with their Alzheimer’s diagnosis or living with some other form of cognitive impairment these alternatives were often confusing, Kallmyer said.

“Imagine not being able to understand why that person is standing on the other side of the window, why they aren’t coming in. They were scared and depending on their cognitive condition sometimes didn’t have the words to describe it,” she said. “It’s a really devastating situation.”

'Huge need' for care workers

As the population ages, experts say that the demand for long-term care services including in-home care services is also expected to grow.

But the long-term care industry has faced a worker shortage that pre-dates the pandemic. There were about 2.3 million people employed as home care workers in the U.S. in 2019, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. The number of job openings for personal care and home healthcare aides is expected to grow by 33% over the next decade, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Recruiting qualified workers like Glover, who was recently recognized by Home Instead for his dedication to clients living with dementia, is a challenge.

Low wages and long hours have made recruitment difficult, according to Jeff Huber, Home Instead CEO, who said the challenge will be to recruit enough quality caregivers as demand for long-term care surges.

“We have this huge need that we need to meet. We want to lead the charge in elevating the caregiving profession to a respected well-compensated vocation and job creation engine in the future,” Huber said.

Meanwhile, the ongoing pandemic has also driven more families to look at ways to keep their loved ones at home as long as possible, according to Lakelyn Hogan, a caregiver, and gerontologist with Home Instead.

“For people living with dementia, memory care can be a great option, but people saw the impact the pandemic had on long-term care,” she said. It goes back to stability, that routine of familiar surroundings. That’s often the desire of the family and the desire of the individual.”